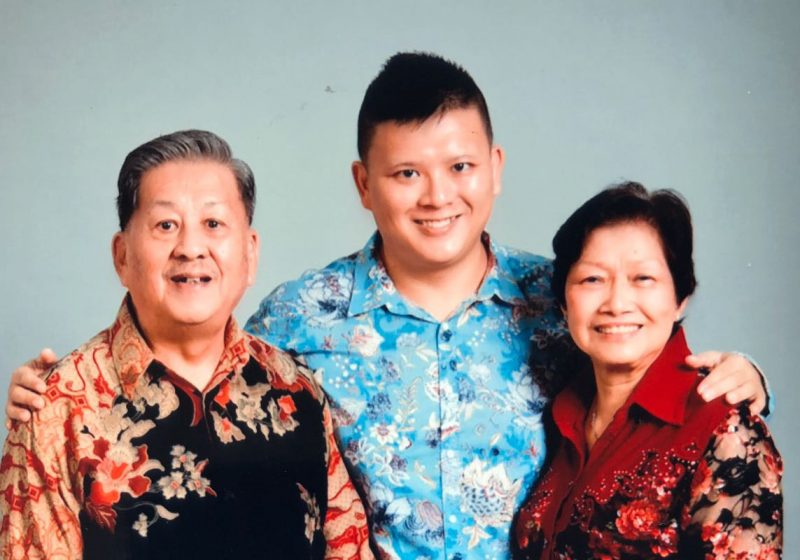

Joanna Sun, from Singapore, shares her memories of growing up with grandma and reflects on seeing grandma’s progress through dementia.

Written By Joanna Sun

My great grandmother lived next door, and I affectionately called her Lau Ma. She had silver-grey hair; a petite slim built lady with tortoiseshell framed spectacles and a signature hair part to the left that was never longer than just passed her ears. She always dressed in a Sam Foo at home, a loose-fitting cotton top fastened with buttons and dark coloured loose, comfortable-looking ankle-length trousers. If she had to out for dinner, she would dawn on a linen or button-front shirt and a simple pair pearl of very tiny pearl earrings.

She spoke Teochew (Chinese dialect), had oatmeal for breakfast, and cooked and ate simple meals which were steamed or stewed accompanied by a bowl of rice. Her beauty regime consisted of moisturising with Hazeline snow which left a tint of rose which hung around her like a subtly hidden bouquet. Sometimes I would have a giggle when she’s in a hurry, and she had applied her moisturiser but hadn’t rubbed it in, and you can see some residue of the waxy clumps of the product on her face. Her drinking glasses always had an aromatic Tieguanyin (Oolong Tea) scent. She loved her plants as much as her Channel eight dramas (local TV Channel) and ritually drank a shot of whisky mixed with a spot of water in the evenings.

She loved gardening so much that she had plants in her home and the rest of her plants were in our little garden too. I remember at five o’clock like clockwork I would hurry out and help water all the plants in a red plastic watering can making several trips to fill it up because the watering can be a third the size of my body. I’d watch her trim and talk to her plants like they were friends of fifty years. She shared with me the pomegranates and papaya that she grew, and she would boil the Clovers in the garden and make a tea out of them.

We had a little ritual in our family; she would be the first person that we’d greet so when I was older every day after school I would pop over and bellow through her window to let her know I am home after school and she would respond with an equally loud acknowledgement. When I think back now, it sure was a quirky ritual.

I didn’t know anything about dementia at that age; I knew the Chinese form of it which people had commonly called 老人癡呆症 (lao ren chi dai zen) but our understanding was a ball of myths and half-truths. Like how the heart would give out and we will pass away so will the brain, that was how it was explained to me when I was little.

Computers in those days were rare, and the internet ran on 56kbps making a shrill ringing sound when it dialled up, books in the library were always three years out of date, and you always had to wait to loan out a good book, mobile phones were the size and weight of a brick, the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) was the biggest hurdle in life. I didn’t think to fact check at that age and took what adults said as the golden truth.

She lived at home and aside from the market, and her hairdresser at Toa Payoh (housing estate in Singapore) and the occasional dinner at a restaurant outside once every few months with family members. Her life was a huge routine of making breakfast, doing house chores, gardening, caring for her pet bird and daily social engagement with family members all during the day who come to visit. If she did forget things, initially she would say she’s old, and it’s okay to be forgetful (Lau liao boh ki ti – old and forgetful in Hokkien, a Chinese dialect).

What she felt, I’d never know, she seemed to be aware of her failing memory but talked about it like it was just another bump in the road and laughed it off. Her high self-efficacy and her ability to remain independent as a result of a familiar environment were certainly a factor I still believe strongly today that kept her going as long as she did.

The first sign that I noticed that something was quite wrong at that young age was when she started to live in her clothes for days, three days in fact and she hadn’t showered. I remember standing beside her outside her bedroom and jokingly saying that she smells, and she needs to shower and went to pull clothes out of her mothball smelling cupboard. She smiled and agreed and went to shower soon after. The adults must have noticed too because I remember people talking about how they were worried about her cooking, and they were talking about cutting off the gas at one point to make sure she would be safe. When I think back now as her brain deteriorated, physiological her body appeared healthy as a horse for a person in their late eighties.

“As a kid, not knowing any better about dementia, I too did not do more to make her experiences, our memories and our relationship any better. I’m wearing my heart on my sleeve here, but I certainly hope that in this day and age of knowledge, education and technology, for anyone, the last memories of their loved ones are peaceful and positive memories.”

The last family reunion dinner I had with my great grandmother, I recall bringing her around to our place for the typical steamboat meal. She sat in the living room waiting while my mother was getting the bits and pieces together, and all she did was repeatedly ask me if I had eaten (Jiak pa buah? – in Hokkien, a Chinese dialect).

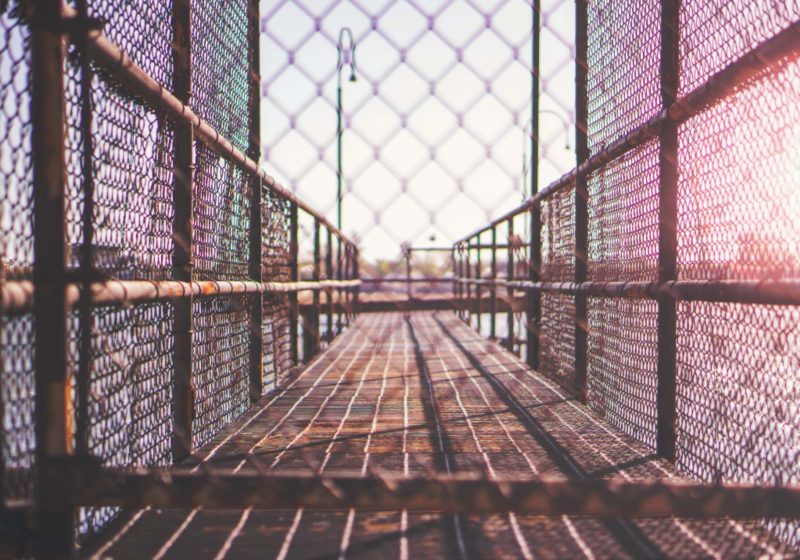

After this dinner, she had gone to live with other relatives while her home was being renovated into a beautiful villa-style residence. Her beige metal grills, colourful tiled floors, hardwood furniture and potted plants were replaced with modern dark brown fences, and rustic sand ceramic floor tiles. The layout of the rooms changed, and it was the same home on the same street, but it looked nothing like the home she had lived in. She came back to stay in the home, and as a child, I recall waking up at night hearing her calling out on numerous occasions. Once I looked at the clock and recalled it was two in the morning, and she kept calling out sounding painfully lost and confused. My parents would talk to her while standing between a wall of hardwood fence to help calm her down. She had a different primary caregiver, and we did not have access to her home, so all they could do was talk to her. My last physical memories of her were the sound of her voice, scared, frantic, confused, lost and alone in the dark, in the night in a seemingly familiar yet unfamiliar environment. Months later, her primary caregivers sold the house, and she stayed with them until she passed in 2009. I never saw her again.

As a kid, not knowing any better about dementia, I too did not do more to make her experiences, our memories and our relationship any better. Dementia is not an isolated condition; it is a condition that transcends family relationships, and social bonds and tests the strength of love, care and unity within the family. I’m wearing my heart on my sleeve here, but I certainly hope that in this day and age of knowledge, education and technology, for anyone, the last memories of their loved ones are peaceful and positive memories.

We just drifted apart as I drifted out of her memory. In my experience, ignorance was certainly not bliss.