This is about what I learned in the early stages of his condition. I’m using examples taken from my own experience and my mistakes. I hope my stumbling will help you find your own path a little more easily.

By Meredith Arthur

My Five Takeaways

This is for those of you who are seeing the signs of memory loss or dementia in your parents. Why? Because it’s starting to happen. I may have been the first, but I won’t be the last. In the past two weeks alone, I’ve spoken with three different friends in their late 30s/early 40s who have alluded to a parent or their in-laws’ confusing behaviour, memory loss, and possible dementia.

I’m using examples taken from my own experience and my mistakes. I hope my stumbling will help you find your own path a little more easily.

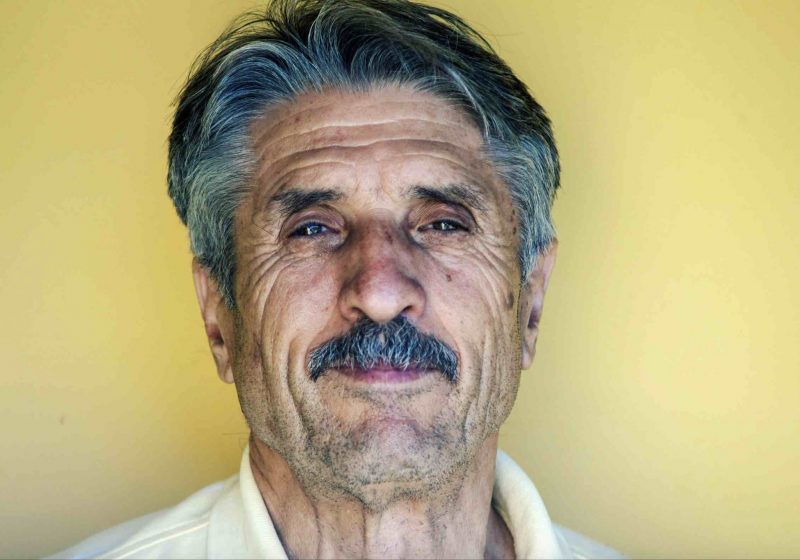

1. “He’s just lazy.”

Before he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, it seemed like my father just didn’t want to do very much. I got up the courage to talk to him about it. I remember it was President’s Day of 2004. I called and asked him what was wrong. I asked him to “come back.”

Takeaway: If your parent seems like they are working too much, playing too much, or drinking too much all of the sudden in their late 60s…it’s not necessarily that they are depressed or choosing not to deal with things. It could be a sign of memory loss. Maybe they’re sticking with familiar patterns but unable to modulate the way they used to. (My brother says: “To me, Dad’s early-stage dementia behaviour was only an exaggerated version of his regular self.”)

I spent years thinking my Dad was lazy. I regret that now.

2. “He can’t mingle.”

My brother, who lived close to my parents during this early stage, says, “The most telling sign of early stage dementia, for me, was Dad’s inability to mingle in groups.”

Takeaway: My brother says, “My takeaway is recognizing that no matter how hard it is on a child to cope with a parent with dementia, the parent with dementia is coping, too.”

I’m painfully aware of how little there is here. I’m giving you scraps really. But it’s more than I had when I set out on my journey. I’m sorry that you are facing this. I know how confusing this all is. I hope that you don’t feel alone.

3. “Diagnosis needed NOW.”

I spent years trying to get my Dad neuropsychological testing. I figured out testing was the place to start by talking with a trusted friend who, luckily enough, was a doctor. I sent her this note from the middle of my impatience in March of 2007:

It’s so frustrating to me that everything is on this constant excuse, “We can’t do that because we are going to SC” or “We only have two months in Ohio so we can’t do it” — just a bunch of excuses as far as I’m concerned, but I think that’s how [my parents] live the way they do.

Her brilliant and measured response: I can understand the frustration with the nomadic parents. It’s hard to know whether people put things off because it isn’t a priority or because they don’t want to face up to them. In this case, I certainly don’t think it will matter to postpone the testing as it’s more likely to give a baseline assessment than change how things are managed right now.

Takeaway 1: If you feel frustrated and want answers, I feel you. Just know that your quest for a diagnosis may be for your own peace of mind more than for the good of your parent (or your supporting/caregiving parent, if you have one). It’s great to understand your parent’s mental baseline, but ultimately, did it matter that my father was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment? I was so focused on taking “the right steps” that I couldn’t hang out with where we were as a family at the time. I just wanted action.

Takeaway 2: Everyone in the family, including you, is adjusting to this change at different speeds. You know this intellectually, but you’ll probably experience it viscerally in the next couple of years. You’re just starting this process of letting go of your parent (and I know that even reading that sentence might hurt, and I’m sorry to be saying it to you). Everyone reacts to the loss differently. Throw a wildcard like un/diagnosed dementia into the mix and then you have heartbreak mixed with a shared project management situation going on. There are no pointers I can give to tell you how to do this the right way. It differs greatly based on your resources — more money and time is better — and location.

4. “I acted weird.”

When I would go home to see my Dad, I was tense. I didn’t know how to avoid asking him questions. I felt like I did everything wrong.

Takeaway: My daughter, who was 3 years old when she last saw my Dad, seemed to understand dementia a lot better than I did. If I were doing it over, I’d take lessons on hanging out from kids. She knew how to be in the moment with ease. When her grandpa would get confused, she’d just reintroduce herself. “I’m Alice.”

5. “I didn’t like advice.”

I was trying to figure out how to get the right information and support in the early stages. I went to a support group for people supporting people with Alz at a hospital in SF. It was all wrong. Just like that sentence.

Takeaway: Find your people, and stick to them. I really wasn’t comforted by hearing how I was supposed to appreciate the new person that dementia gave me. Other people might be, though. If this post isn’t helping you close it right now and forget you ever read it. Ditto with how people respond to news of your parent’s sickness. Close, delete, and forget the responses from people that don’t fit who you are.

To caregivers out there

I’m painfully aware of how little there is here. I’m giving you scraps really. But it’s more than I had when I set out on my journey. I’m sorry that you are facing this. I know how confusing this all is. I hope that you don’t feel alone.

Meredith Arthur is based in San Francisco. She’s the editor of Invisible Illness and Beautiful Voyager, a website for overthinkers, people pleasers, and perfectionists. Find her on Twitter at @bevoya.