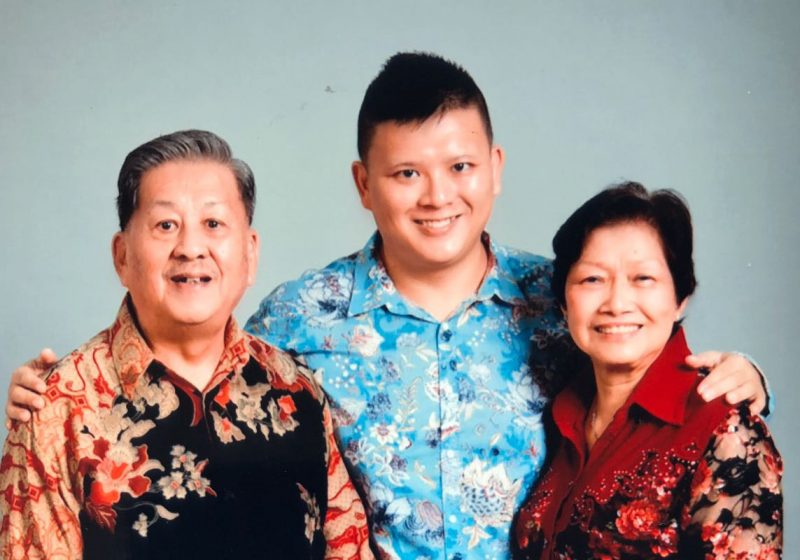

Julia is 26 and caring for her grandfather with dementia in Canada. She brings us through her journey in growing up with her grandfather, caring for him with dementia, and her message for other caregivers out there.

By Julia Dima

My name is Julia, and I help care for my grandfather, who has vascular dementia. My caregiving role has shifted as my grandpa’s age and the disease progressed. In the early stages, I assisted my mum and grandmother in providing care when my grandfather lived in the home. He lived with my grandmother, and I provided secondary/tertiary care.

Caring for my grandfather

About four years ago, my grandmother was struggling with severe caregiver burnout, and my grandpa was moved into a long-term care facility. While there, my roles shifted to more hands-on care. Due to language barriers and the struggles with dementia we all know too well, the staff often had a tough time providing care to grandpa.

I quit my newly-started career, moved back to our home city where he was living, and helped the family out by visiting my grandpa daily, helping with feeding, changing medications, and quality of life enrichment activities. About two years on, grandpa had a number of mini-strokes that took away his mobility.

Since then, grandpa has moved into a new long-term care facility (which we love!), and thanks to the dedicated hard-working staff, our roles have shifted, and now my main role is providing my grandpa with quality of life activities, and spending time with him in his final, palliative stage of life.

What dementia means to me

To me, dementia means a lot of things. It means relearning everything you think you know about your loved one. It means having to radically shift your paradigms when it comes to the relationships in our family. It means having to learn a whole new language – yes, speaking dementia is a real thing! It means learning so much, trying to help others learn, and it has given meaning to my life.

Along our struggle with dementia, and navigating the healthcare services in our province, it has become incredibly important to me to increase awareness, understanding, and acceptance for people with dementia, to quash myths about dementia, and to help people of my generation (I’m 26) understand why we should care about dementia and mobilize by voting for better senior care, better dementia strategies, and increased public education. I often feel like an odd duck when it comes to my experiences with my grandpa’s dementia.

“With dementia, we faced moments of anger, confusion, hallucinations, and all the other early signs of the condition. But dementia also helped him. It took away many of his angry memories, it helped him see what was right in front of him, and not think about all that was behind him.”

Growing up, I knew I was well-loved by him, as he helped raise me, since my father was not around, and my mom was a young woman pursuing education. But grandpa was harsh, he would yell, he would smack my fingers with a ruler if I was out of line, he would brood quietly, and every woman in my family has at least a few memories of this harsh man we were all very scared of at times.

Dementia taking away the bad memories

I did not know so much of his anger came from what happened to him. The cyclical abuse and violence he faced had a generational impact on all of us, but he carried it deep inside of him without sharing too much. He relocated to Canada so that his wife and daughters would never have to experience what he had. He paved the way for us to live better lives while carrying his pain inside.

With dementia, we faced moments of anger, confusion, hallucinations, and all the other early signs of the condition. But dementia also helped him. It took away many of his angry memories, it helped him see what was right in front of him, and not think about all that was behind him. He turned into someone who laughs at puppies playing or finds simple joy in a flower growing in a garden. It gave him some peace, something he rightfully deserves.

Today, my grandpa will spend hours watching the birds come to the feeder outside his window or the small rabbit who visits the courtyard outside his room.

He doesn’t believe he’s in prison anymore (a common PTSD flashback he used to have). In that sense, dementia has been a gift for my grandpa, who spent his life tormented by the ugly dark corner of his mind. For that, unlike many many people, I’ve been thankful for the disease, because, though it has turned off lights in different corners of his brain, it has also extinguished the fires in other corners, that burned him from the inside out.

Caregiver guilt, burnout, and depression

I’ve faced a number of challenges as a caregiver, like everyone who has experience with the disease. The most common things have been caregiver burnout and caregiver guilt. I know, and preach loudly to others struggling with caregiving, that you cannot pour from an empty cup, so you must find ways to prioritize self-care. Of course, it’s much easier to give that advice than to follow it yourself.

I have lived with major depressive disorder most of my life, which can make the balance of work, life, caregiving, and basic survival very difficult at times. I’ve had many days where I struggle for hours to get out of bed, where showers and cooking meals feel like running marathons. Where I cry for no reason, or can’t feel anything at all. I’ve attempted suicide, and I’ve engaged in self-harm and substance abuse to cope with my illness.

My grandpa has never had a clue that I am depressed. I have, out of necessity, hidden my illness from my grandparents. At times, I’ve taken “self-care” days away from grandpa, knowing that the care, and the sadness I absorb in watching the disease impact him, has a negative impact on my mental health. This is a way to cope with and address when I am feeling burned out. It’s immediately followed by that other pleasant little emotion, caregiver guilt! When I take time to care for myself, if I learn that my grandpa has had a bad day, or he did not eat, I am immediately filled with guilt for not being there.

On an intellectual level, I recognize that the guilt is not warranted, and that it is healthy and necessary to care for myself, but on a personal and emotional level, it’s a different story. One of the symptoms of depression is feeling like a failure or a burden to people in your life. This symptom impacts me daily, and becomes heightened when combined with caregiver guilt.

The ongoing struggle

This is an ongoing struggle, and I’m sure it always will be, so I don’t profess to have any solutions for others dealing with these feelings, other than encouragement that every caregiver out there, no matter how much or little you’re able to do, is exceptional, important, loved, and deserving of life and happiness. I try my best to follow this advice, and find purpose and a reason to keep living if I can help others through their struggles.

Balancing life and care is always difficult, like any balance. In addition to helping care for grandpa, I also help care for my grandma, who has cancer, work full time, have a loving long-term relationship, and run a small side business selling my visual art. The balancing act sometimes feels like juggling knives while battling a hangover! Inevitably, something falls through the cracks, and I have to make tough decisions about what to prioritize, and it usually has consequences. But my coping mechanism for balancing life and care is to thoughtfully engage in what makes me happy. I believe that art and caring for animals are incredible natural therapies. I try to use any of my spare time to create something with my hands, or volunteer with animals. Self-care will mean different things to different people, but I encourage all caregivers to find what they are passionate about, and engage in it, as you will come back to your caregiving renewed and refreshed.

“I want other caregivers to remember that you are not alone, that there are so many of us all over the world, who know exactly what you mean, exactly what you feel, and exactly how alone you feel. Which means you’re not alone.”

I want other caregivers to remember that you are not alone

My message to other caregivers is that you’re doing great. I know that you, like me, are bombarded by feelings of guilt, sadness, resentment, fear, and hopelessness. These emotions can feel so overwhelming, especially since your loved one may not be able to express how much they love you, and how thankful they really are for you (In fact, sometimes it’s the opposite, and nothing can take away the emotional scar of having your loved one telling you they hate you, or want you to leave).

You must ensure that you are healthy, and happy, and doing what you can, even if it’s a small thing like enjoying a cup of tea, or buying a new sweater, to keep yourself grounded, and remind yourself that you have value and worth. Whatever you do for your loved one, it is an incredible thing, it is selfless, and to me, you are heroes for your dedication to helping your loved one, and creating awareness about dementia.

Dementia is hard, it is the long goodbye, it has an inevitable ending that we all must face. Unlike other illnesses, where there are cures, where medical intervention can kill the illness, dementia can feel totally hopeless. It can feel isolating, and you and your loved one can feel very alone in the world. I want other caregivers to remember that you are not alone, that there are so many of us all over the world, who know exactly what you mean, exactly what you feel, and exactly how alone you feel. Which means you’re not alone.

Whether you’re 20 years old, or 80 years old, you are loved and supported, and I, along with all these other great people in the Project We Forget community network are here for you, whether you need advice, help, or just somewhere where you can share what you feel, and just need a good cry. Don’t give up, don’t give in to hopelessness, believe in hope and love, and value the small beautiful moments in this life, and in your journey.