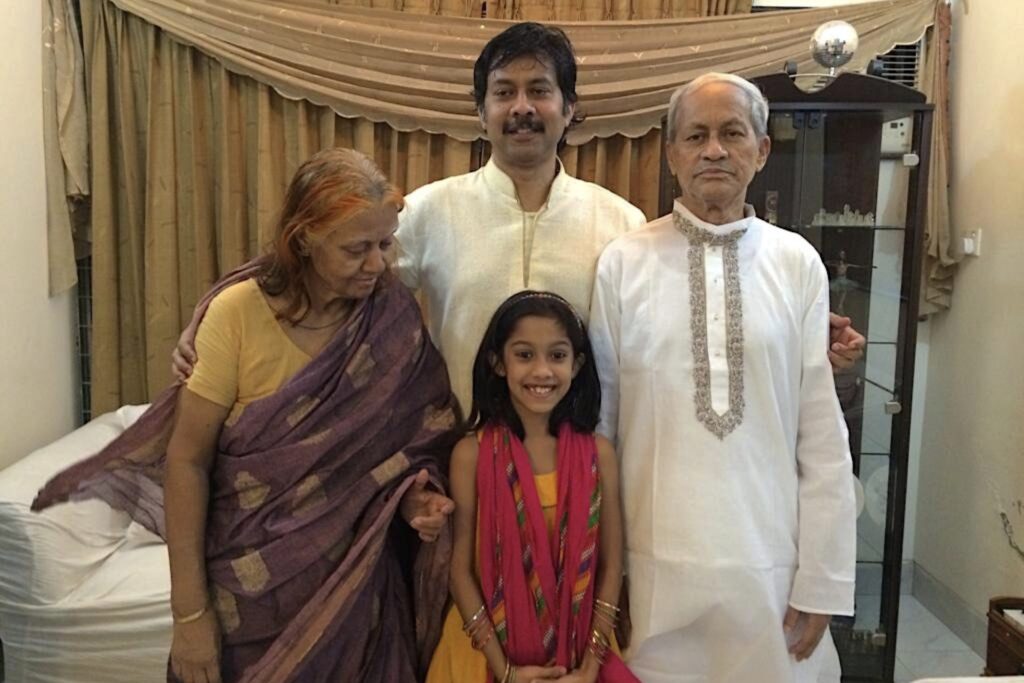

“I grew up with my grandmother, yet sometimes it feels like I never knew her at all. After all these years that I had been looking for a way to say goodbye to someone who had already left us a long time ago, I finally realised that I didn’t actually want to say goodbye, but thank you instead.”

Contributed by Aaliya Syeda

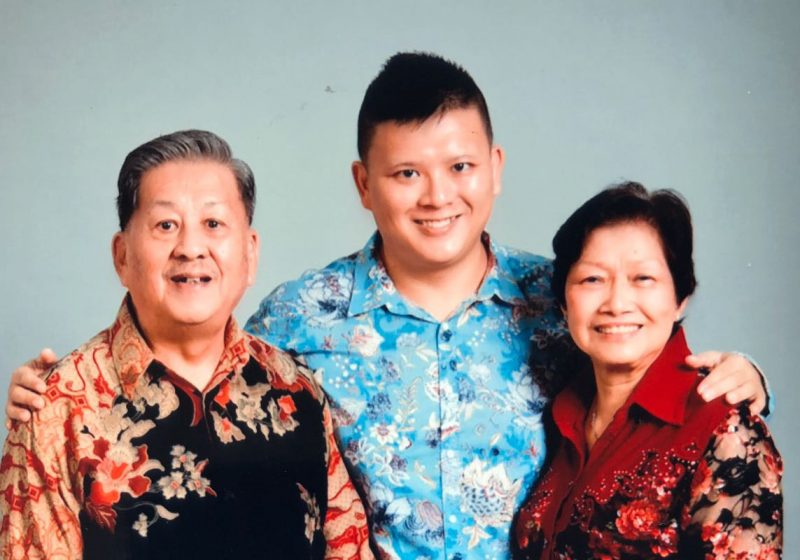

My Dadu and I

I was seven years old when my grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Being seven years old meant that I was deemed too young to understand what it was, and for that I never really had a specific moment in my life where I found out that my grandma would forget me one day. Perhaps my parents assumed that when I was older, I wouldn’t be able to recall a time in which she remembered me anyway, so why bother explaining that her grandmother was sick to a child whose sense of normal hadn’t even been established yet? They were right though. I didn’t remember.

Instead, I grew up with it having organically grown on me, that my grandma didn’t know who I was and that sometimes she’d say things that didn’t make any sense, but there was nothing wrong or unusual in that because that was dadu for me.

My experiences were shaped through observations – through watching my father take care of his mother like he took care of me, and watching the parental roles of nature be subverted in the most wholesome yet heartbreaking way.

My Father’s Experiences Became My Own

Over time, the word Alzheimer’s implanted itself in my head, but I still didn’t understand it well enough to ascertain the depths of it. My experiences were shaped through observations – through watching my father take care of his mother like he took care of me and watching the parental roles of nature be subverted in the most wholesome yet heartbreaking way.

The way that during lunch, he would debone my fish for me and then debone hers as well, as if we were the same. Somehow, through observing, my father’s experiences became my own. And as I grew older, our realities merged into one. I ended up on the same page as the rest of the adults, only to realise that it was no different than being a child – oblivious, even then, to what was happening to her.

In all likelihood, it was the hope that hurt the most, but soon we learned how to mask that too, pretending that, over time, her lack of response meant nothing to us anymore.

It Seems Like Only Yesterday

They don’t talk about these things in Bangladesh. The doctors – they stamp a diagnosis on the forehead of your loved one and send them home to battle the disease by themselves. If you’re lucky, you’ll probably get some sort of guidebook to tell you to not lose hope along the way, but even that was the worst possible advice you could give. I wish they had told us that hope should have been the absolute last thing we had on our minds. I remember what this hope felt like as if it was just yesterday, but in reality, it’s been nearly 4 years since…

“Where is Aaliya? Can you say Aa-li-ya?” My father would ask my grandma, over and over again, like it was a ritual to repeat my name and wait with lingering hope as she would nod blankly and then look away.

Sometimes, I couldn’t help but think she was trying to form words, and as her lips would move ever so slightly, the expectations that sunk into the silence of the room would be alive once again, reborn from the disappointment that we grew accustomed to hiding. I’d sit there next to her, watching my father wait patiently for her to say something, and praying that by some miracle, she would turn to me and say, “there’s Aaliya, right there”, but that never happened.

In all likelihood, it was the hope that hurt the most, but soon we learned how to mask that too, pretending that, over time, her lack of response meant nothing to us anymore.

My memories of my grandmother exist in achronological fragments of a story that I don’t imagine I will ever be able to retell linearly. Because Alzheimer’s, in retrospect, was a cycle of loss and desperation, in between which we would sometimes get her back for a promising ten seconds and then lose her all over again as she slowly succumbed back into the monotony of her daily lifestyle.

I realise now that although we lived together, I grew up completely separated from her reality while she was completely detached from ours. Looking back, I wish I was older back then. To have been able to explain to my grandfather that it wasn’t her fault that she couldn’t understand him and that it wasn’t his fault either. To have been able to support my father as he took care of her without really knowing what he was supposed to do. 10 years ago, we didn’t have the luxury of Google or Facebook Caregiver Groups or free dementia handbooks that are available nowadays.

Because to say 10 years ago in a country like Bangladesh would be equivalent to saying 50 years back in Singapore – which is where I live today. Back then, we didn’t know that music was such a powerful medium for improving the emotional well-being of someone with Alzheimer’s, yet my father would still play her favourite Bengali songs every day because his instincts told him it would make her feel better. Maybe remember?

Everyday that I make another elderly person with dementia smile, or work to increase youth awareness of dementia in Bangladesh is a reminder to myself that she did exist and that I loved her very much.

Lack of Accessible Caregivers’ Education in Bangladesh

They don’t know about these things in Bangladesh. The caregivers aren’t educated enough to understand Alzheimer’s nor are they sensitive enough to care. I remember being little and watching how my grandma’s caregivers used to treat her when my father was at work. I remember them calling her “crazy” and screaming at her for not being responsive at times.

They’d talk about her as if she wasn’t in the room and then make up stories to tell my father when he returned home later in the evening. “She was asking for you today” they’d tell him, “she remembered Aaliya by name today”. But I knew it didn’t happen. They didn’t realise that what they claimed couldn’t have happened. But I didn’t blame them, for we were all ignorant after all. I reckon things haven’t changed much there. But I wouldn’t know, I haven’t been back there since 2019.

I grew up with my grandmother, yet sometimes it feels like I never knew her at all. After all these years that I had been looking for a way to say goodbye to someone who had already left us a long time ago, I finally realised that I didn’t want to say goodbye, but thank you instead. For inspiring me and making me who I am today and who I want to be. Every day that I make another elderly person with dementia smile or work to increase youth awareness of dementia in Bangladesh reminds me that she did exist and that I loved her very much.