“Caregivers of all ages need support. Shouldn’t we simply support all caregivers?” A belief that all caregivers have the exact same set of needs and experiences is simply inaccurate and short-sighted.

By Feylyn Lewis

“Caregivers of ALL ages need support. Shouldn’t we simply support ALL caregivers?”

When I speak to the community about the needs of child and young adult caregivers, I often hear those two remarks in response. On the surface, both appear to offer unreserved support for caregivers. In reality, the messages have polar opposite intentions. The former statement says that no caregiver, of any age, should be forgotten or overlooked in regards to support.

The latter statement implies that it’s nonsensical to point out the diversity of needs amongst caregivers – it cheerily exclaims, “Let’s just help everyone!” I wholeheartedly agree with the sentiment of the first. However, the second statement demonstrates naiveté at best and callous indifference at worst.

Similar to the discourse surrounding #BlackLivesMatter and #AllLivesMatter, the idea that younger age caregivers have distinctive needs and experiences —and therefore, require different, targeted approaches to support — from their older caregiving counterparts is one that somehow prompts alarm and scrutiny.

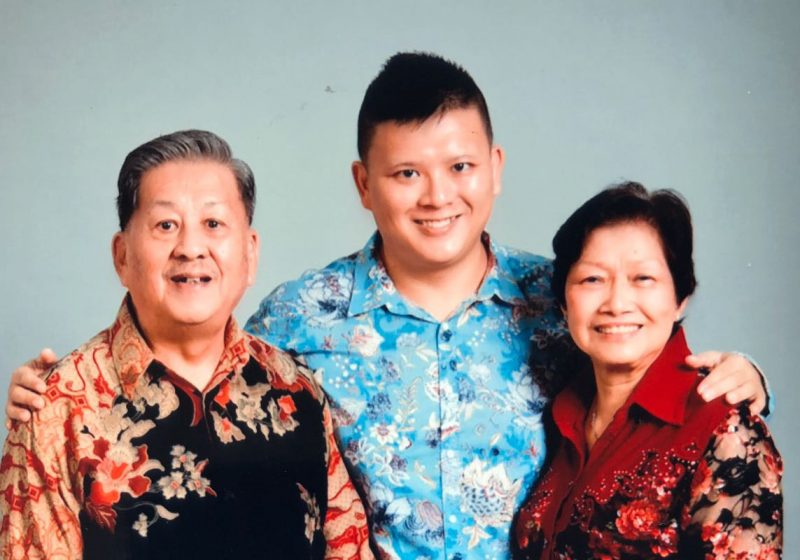

Some feel that the attention given to younger age caregivers detracts from the ability to raise awareness about all caregivers, particularly those in the Baby Boomer population. By highlighting the needs of one subset of caregivers, i.e., children and young adults, there is a fear that the remaining, older aged caregivers will be overlooked in obtaining services and policy recognition. Others feel that a focus on young caregivers is divisive, believing that advocacy for one particular group of caregivers will lend itself towards exclusionary practices.

Thankfully, caregiving advocacy is not a zero sum game. A belief that all caregivers have the exact same set of needs and experiences is simply inaccurate and short-sighted.

Previous research has overwhelmingly shown that young caregivers express distinctive needs and desire targeted support for their age group. They may feel out of place in the “typical” support group, and the need to have discussions surrounding their unique experiences (e.g., juggling homework, dating, and jobs in the midst of caregiving) go unfulfilled.

Their young age has not afforded them the opportunity to secure stable careers with financial security or assets such as savings accounts, stocks, and property that can be leveraged in times of financial strain. Young caregivers are providing for their families in a life stage in which society normatively expects them to be wild, free, and independent; this is the time set apart to “find yourself”, develop relationships with friends and romantic partners, and make decisions on educational and career paths. Young caregivers are faced with that same set of expectations, but they must make choices regarding their personal life plans while also considering the needs of their families.

The 6.9 million children and young adults in the United States who provide care for their families are largely hidden from the view of policy-makers and supportive organizations. Young caregivers suffer societal stigmatization due to views related to their age range and roles as primary versus secondary caregivers.

I am often told that young people are too narcissistic to be caregivers, and that those who share caregiving responsibilities with other family members, or provide care on the weekends or school breaks don’t “count” as caregivers.

Child caregivers face a particularly disparaging battle to receiving support: some families with child caregivers fear the threat of social services issuing charges of neglect, so they choose to keep quiet about their children’s caregiving roles. The argument to support all caregivers perpetuates this cycle of invisibility and silence, and young caregivers continue to lose out.

Yes, all caregivers matter. Yes, caregivers of every age need support and recognition. The young will one day become old. In our fight to raise the profile of caregivers, let us not forget that specialized attention for some does not diminish the importance of all.

Feylyn Lewis is a post-doctoral research fellow at the University of Sussex in England. Her doctoral research at the University of Birmingham focused on the identity development of young adult caregivers living in the United Kingdom and the United States. She was also a young caregiver for her mother during her childhood.