Christmas can be a stressful time for hosts and guests alike, and it’s more so for carers of people living with dementia. Through Tom and Nola’s story, I hope that their strategies will suggest things other families can do for a better Christmas.

By Lee-Fay Low

Christmas can be a stressful time for hosts and guests alike, and it’s more so for carers of people living with dementia. It’s difficult to give general advice about how to get through the holiday season with as little fuss as possible because everyone is unique, and the various types and stages of dementia affect behaviour in different ways.

So I’m going to tell you a story of how one couple is getting through. Hopefully, their strategies will suggest things other families can do for a better Christmas.

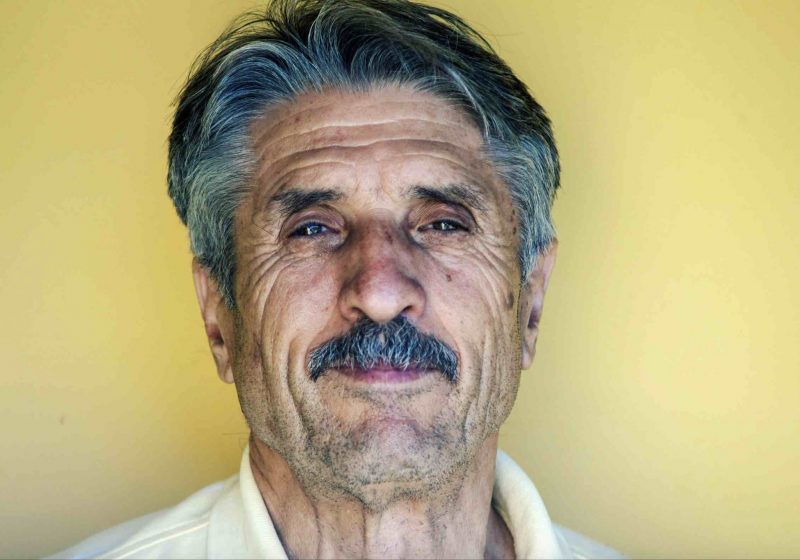

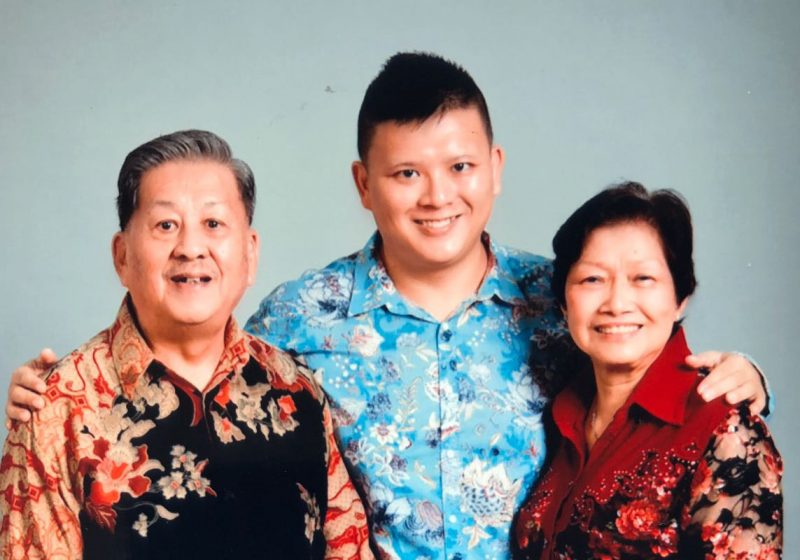

Tom and Nola are not real people. Their portraits below are based on my experience working with people with dementia, and on conversations, I’ve had with these people, their carers and service providers about how to cope at Christmas time.

Tailoring Christmas

Tom was diagnosed with dementia about three years ago.

“My memory is not so good now,” he says. But Nola, his wife and carer, says that he’s still sociable and enjoys food and company.

“Tom’s difficulty is that he can’t follow most conversations, remember people’s names and needs help finding his way around. He likes me to be around all the time because he seems to be worried about something happening, and can’t make even small decisions such as what he wants to eat from the fridge.”

After a stressful and exhausting experience last year, Nola has decided not to host Christmas this time around.

“This year we’re going to break with tradition and not have the extended family over for lunch,” Nola says.

“Tom doesn’t cope well when there’s a group of more than four people, especially when the conversation is going fast and people are excited. He either talks out of turn and says something inappropriate, or wanders off, and I know he finds it frustrating not fitting in. He gets tired after an hour and asks to go home.”

“If I’m stressed, Tom senses this and gets anxious too. So it’s better for both of us if we have quieter celebrations this year.”

This tendency for mood to be transferred between people is known as emotional contagion, and it’s enhanced in people with dementia.

Changing expectations

Nola didn’t find it easy to tell her three children about their decision.

“I felt like I was letting the family down. I think they felt a little abandoned.”

“They tried to persuade me to have it at our place still and they would help out more, but I know it would still be difficult to cope with for Tom. The grandkids get so excited on the day and scream and run around.”

“My daughter has agreed to have Christmas at her place. Tom and I are going to arrive late morning because this is his best time. I’m hoping that he’ll be happy to have an afternoon rest in the bedroom with some quiet music so that I can relax and not worry about him and be with the family. But if he’s not happy with that then we’ll just go home.”

“My children are all going to individually have lunch with us that week so that Tom and I get to have some time with them in a quieter environment.”

“Leading up to Christmas we’ve been finding Tom activities that he can do with each of us within his abilities. One daughter has been bringing her Christmas cards and getting Tom to address the envelopes and put on the stamps. This got him reminiscing about the past few Christmases.”

“We get lots of visitors this time of year and I’ve been asking each person who comes to spend five minutes talking one-on-one with Tom. I remind them that it takes him a little bit of time to respond in conversations sometimes and to just give him this time.”

“The grandkids are now really good at having this special ‘Pop time’ and often bring something they’ve made at school to show him. He enjoyed singing Christmas carols with Christa (a granddaughter) last week and remembers all the words.”

“People often ask me what to give Tom, and I have been asking them to give him the gift of their company.”

Nola often suggests activities that Tom likes and can do that he and the visitor can do together.

“It’s also a present of time to myself when someone takes Tom out, or are keeping him occupied and content.”

“The grandkids used to think that because Tom didn’t remember their visits that it was better to bring him presents because then he would have something to remember them by. I explained that the happy warm feelings bring chemical changes in his brain which remain even though the memory is lost.”

Advice and tips

Hopefully, this little vignette is a useful tool to start thinking about how you can tailor your Christmas celebrations to accommodate the person with dementia in your family. Here are some tips for carers of people living with dementia:

- Have realistic expectations of what you have the time and energy to do, and what the person with dementia has the ability to do.

- Communicate with family and friends about how things may be different this year.

- Ask for help, remember your tiredness and agitation is contagious.

- Plan somewhere quiet where the person with dementia can have some “time out” from the family celebration.

- Give family and friends activities they can do with the person with dementia.

- Get family and friends to give you respite so that you can enjoy the Christmas season too.

- Ask family and friends to spend a little one-on-one time with the person with dementia.

- Let others know that the person with dementia may value gifts of company rather than material goods.

Dr Lee-Fay Low (BSc Psych (Hons), PhD) is A/Prof in Ageing and Health in the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Sydney. She leads the Community Care research node for the Dementia Collaborative Research Centre – Assessment and Better Care. She has published 70 peer-reviewed papers, and six book chapters, and been awarded over three million dollars in competitive grant funding. She has also written a book “Live and Laugh with dementia” for family and professional carers and people with early dementia.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.