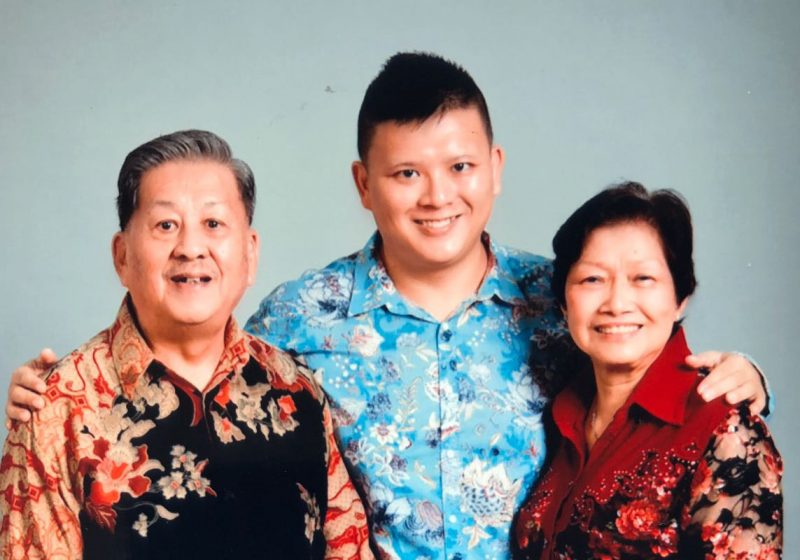

Keir Gravil, from the UK, was 26 when his father was diagnosed with young-onset Alzheimer’s. He brings us through his journey from the point of diagnosis to realisation and shares how he and his family are currently facing the road ahead together.

By Keir Gravil

In 2012, my dad’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis came to me not as some monumental shock or sense of overwhelming tragedy, but as something to which I had no idea how to react. It had simply never occurred to me that something like this could happen in life; no family member I knew had ever suffered from such a condition. What was it that I had just been told? What did it mean? I had plenty of questions, but the most confusing aspect of my father’s diagnosis was the gaping chasm between what I was supposed to feel, and what I did feel.

What I was supposed to feel, and what I did feel

There are many ways of reacting to such news and there are many ways society tells you how to react and what you’re supposed to feel. The archetypal response often involves tears and an outpouring of grief, and that works for many people. For me, the closest description to my reaction was bewilderment and disbelief. There were no tears at first, it was mostly denial and guilt. I felt guilty that I didn’t feel anything more; I was fairly numb and my first instinct was to just carry on as normal and ignore it.

Of course, I knew what Alzheimer’s was; I knew it was a terminal illness and that there was no cure. This, I said to myself, was something that happened to other families, not mine. I carried on as if I’d been told nothing. It took me a long time to accept that this was OK, that my reaction to this news was just as valid and acceptable as any other. It was part of the process of rationalising the situation in which my family found itself. I’d snap out of it eventually but until then I just needed time to think. The few hundred miles distance between my parents and I meant that I wasn’t really faced with the reality of the situation immediately and I didn’t truly understand the gravity of the illness.

My realisation and the first moment that I felt I understood

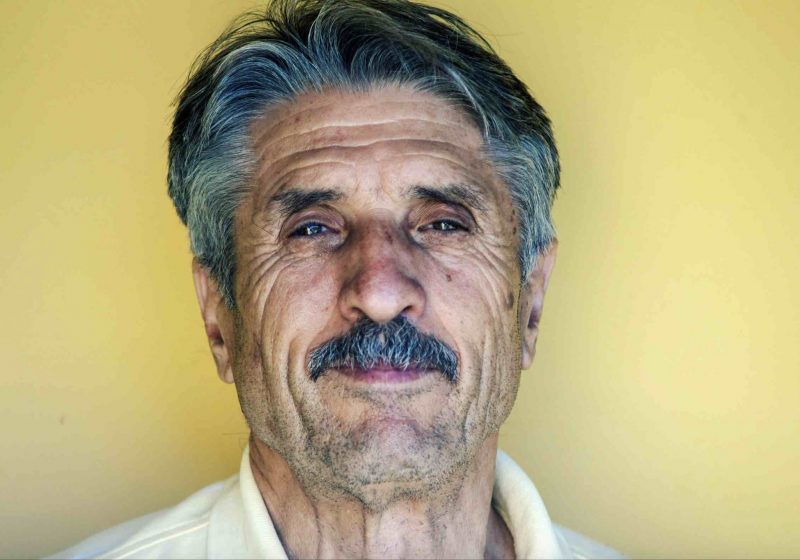

The first time the situation really hit me was when my parents visited my apartment for a week. My dad had spent decades working as a chef in the British Army and also for a private girls’ school. He was amazing at what he did, even baking a Christmas cake for the Queen (a story he often told). There was no doubt he knew his way around a kitchen. I’d noticed that he’d been acting oddly for a few days, but I put that down to the fact that both my mum and dad were tired and they were visiting somewhere new.

I did notice that my dad’s ability to recall information wasn’t great; it was as though everything was just on the tip of his tongue. We all experience that from time to time, where you’re aware that you know something but can’t quite recall it specifically. My dad was slightly different; this problem was constant. He needed more prompting than usual but as soon as you mentioned what he needed to remember, it was like unblocking a pipe. The information came gushing through again and it was all OK. It was all OK until he offered to cook dinner.

The clarity of this moment is something that I will take with me throughout the rest of my life. Ironically, I remember everything about it to the finest detail like a photo stuck inside my head. The moment he stepped over to my cooker and couldn’t work out how to use it. I was about to step over to help him when my mum quietly pulled me back and asked me to just observe; it was only for a minute but it felt like ten. My dad just stood there looking at the cooker, twisting some of the dials, lifting the hob plates to look under them. He couldn’t work out how to use it at all.

A man whose life had been spent in every type of kitchen imaginable from the comforts of home to the middle of the Saudi desert couldn’t work out how to use my simple cooker. It was then that I realised how serious this illness was, what it meant for him and that it wasn’t something that was going to just go away. It had already claimed part of his life that many of us had taken for granted. This was, for me, a turning point in my realisation and understanding of Alzheimer’s and its consequences. It was also the first moment that I felt I understood the road ahead.

The choice to take the burden alone or open it up to others

Life changes when a relative is diagnosed with an illness but not in the way many think. You learn a lot about your own family that you never knew before. Every family has areas within them that are private but when one is diagnosed with an illness there is a choice: take the burden alone or open it up to others. The thing I was least prepared for was dealing with aspects of family life that had simply been none of my business before: finances, legal matters, wills and personal medical issues. It can be a lot to take in. In many cultures and especially in Britain, finances are deeply private. The idea of being involved with those of my parents was scary; I’d never had any interest in knowing their private business like this but now I had no choice.

It took a lot of adjustment to go from discussing how one’s day was to talking about having ‘Power of Attorney’ or talking about my parents’ pensions. Again, I had to just go along with it and learn as I went. I now held the reins of the family along with my Mum; I was totally unprepared for this at first. Who am I, as a son, to decide what is best for one of my parents? They raised me, they looked after me for my whole life and made decisions that led me to where I am today. It felt surreal for this role to be reversed so suddenly. Here I was making decisions that not only affected my life, but those of my parents.

Mum’s strength and how I choose to support her

As for my Mum, I doubt I’ll ever understand how the diagnosis affected her. Being a nurse, I imagine she’s faced with the prospect of telling loved ones bad news regularly but to be on the receiving end of it must still be unimaginable. I’ve always thought there’s an element of protection that goes into the news she tells me. Any parent would want to shield their child from pain and harm, it’s only natural and I expected it. One thing I’ve had to learn to live with is finding out information about my dad from other sources too. It’s difficult enough for my mum to look after him and still work as a nurse, let alone having to relive every moment by telling me about it. I’ve discovered that the best thing I can do is just be there when I’m needed. The less my mum has to worry about me and what I’m doing the better so long as I can help when I’m asked to.

It’s difficult; it often feels like I’m walking a tightrope between making sure my own life is in order and being there for my mum as best I can. Everybody has to try to carry on as well as deal with my dad’s illness and when you’re learning along the way, it can be extremely challenging to work out what to do. After all, bills still need to be paid and we all still need to eat with a roof over our heads. Beyond life’s necessities, we all still need to find time for fun and relaxation as well.

The road ahead

It has been five years since my Dad was first diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease at the age of 53. Since these first few months, the learning curve has flattened out, although there are still challenges to everyday life and questions that are difficult to answer. Sometimes when people ask me what my dad does for a living, I don’t know whether to say he is a chef or he was a chef. Simple grammar becomes a debate as to whether you’ve given up or not. We’ve had some funny moments too. Simple things, such as when my dad offers to make a cup of tea (multiple times) and then eventually arrives with a cup of coffee, or nothing at all, the absurdity can make you both laugh together. My mum’s closest friends have helped her so much too and I’ve been truly amazed by how many people have come together to help out. You really do find out your closest friends in times of difficulty.

I try not to think about what is to come too much; whilst it’s sensible to plan ahead there really is no point in dwelling too much about the inevitable. Enjoying life’s moments has become more of a priority for the family and it’s amazing how aspects of life that used to worry me now seem insignificant. If I’ve gained one thing from the journey so far it’s a better sense of perspective. We all know how the journey will end, but the way we get there is up to us.