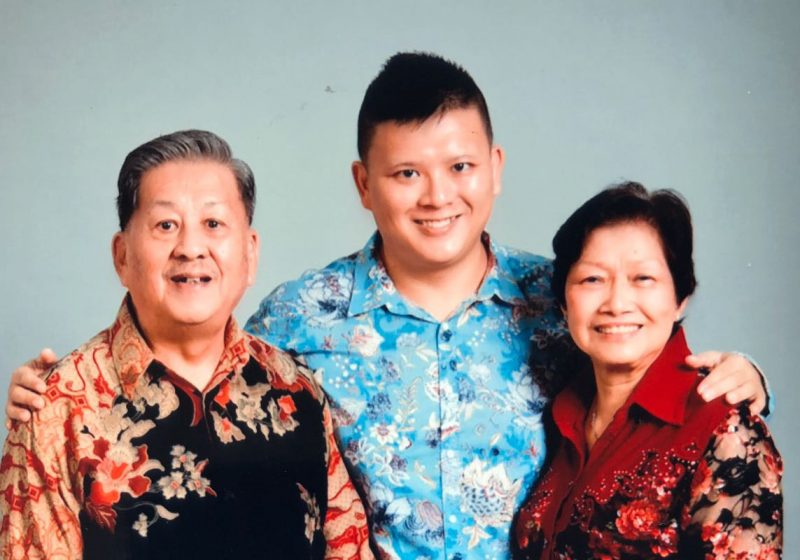

Liza Futerman was in her 20s when her mom, based in Israel, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. She shares her journey of loving her mom with dementia and her search for knowledge and support as a younger caregiver.

By Liza Futerman

Empty shells – living dead – a never-ending funeral – these were some of the terms that were used to describe dementia to me following my mom’s diagnosis with Alzheimer’s Disease at the age of 58 in April 2014.

The signs were there for a while. About a year before the official diagnosis, which was treated like a verdict, I realised neither my mother, father nor I had the tools to cope with her new and unstable condition.

I was motivated to learn more about the medical condition and find effective ways to support my mom. I wanted to understand what she was going through and how I could help her and my father, who assumed the role of the primary care partner.However, whenever I Googled the words Alzheimer’s or dementia, I was bombarded with countless articles, websites, commercials etc. telling me how grim our family’s situation was and how devastating our future is bound to be. At this stage, it dawned on me that the tragedy-infused language about dementia wasn’t helping me much. Nor was it helping my parents.

I wished to do something to help my mom to regain some of her self-worth—something that she has been losing gradually over the decade she was living with MCI and undiagnosed Alzheimer’s. Getting things wrong made her doubt herself, every day a bit more, she got to a point that everything she said was followed by an uncertain look through which she was seeking validation—validation that we were not in a position to offer as we did not have the tools to do so.

We were busy bereaving a person that was still very much alive.

Israel’s Alzheimer’s Association’s (EMDA) headquarters are located in the centre of Israel, while my parents live in Beer Sheva, a peripheral city that was not getting the services that the association works tirelessly to provide. Since mom’s diagnosis, we learnt that there are some services offered in my hometown but having tried them out, we have come to realise that these were not as helpful as we had hoped.

Later I learnt, that people with Alzheimer’s experience the condition in a myriad of ways, something that is rarely addressed by dementia specialists and dementia care practitioners. In fact, I realised that more often than not, we don’t even know what kind of help we are searching for. We have gained some knowledge and understanding of the condition since mom’s diagnosis, but often, we still find ourselves utterly helpless, trying to navigate the health and welfare systems and coming to terms with our loss and grief.

For me, as a young caregiver, I realised that there were no support groups that were targeting my age group. I felt very much alone in my experiences. In many ways it felt like the ground was crumbling right under my feet while trying to handle caregiving and keeping my life together. I desperately wanted to do something, to shout out to the world that I exist, that we exist, and that we need help. But this battle of getting help is hard when fighting it alone, when even the doctors who diagnose your mom tell you that ‘it could be something else, she’s too young of age to get Alzheimer’s.’ And soon after they add: ‘there’s nothing much that you can do, just make sure you take care of yourself.’

Taking care of yourself is not easy when your mind is set on taking care of someone you love, especially when you’re not given the right tools. I wished for a community, for someone who went through what I was going through to advise me beyond ‘there’s nothing you can do’. I wished for people to hurt with, to laugh with, to be with without judgment, to just be. This is why finding out about Melissa’s story and the work of Project We Forgot (PWF) was such a valuable resource. Young people globally are sharing their stories and pledging to take action by voicing their experiences. It helps us feel less alone in this journey of caring for those we love.