Before we start to judge and think that people who wish death upon their ailing parents are terrible people, take a step back. Who are we to judge when we have not had the traumatic experience of watching somebody whom we love wither before our very eyes? What gives us the right to stigmatise when it is hard to do what caregivers do? What would you do when the unthinkable befalls you?

By Y.J Yeap

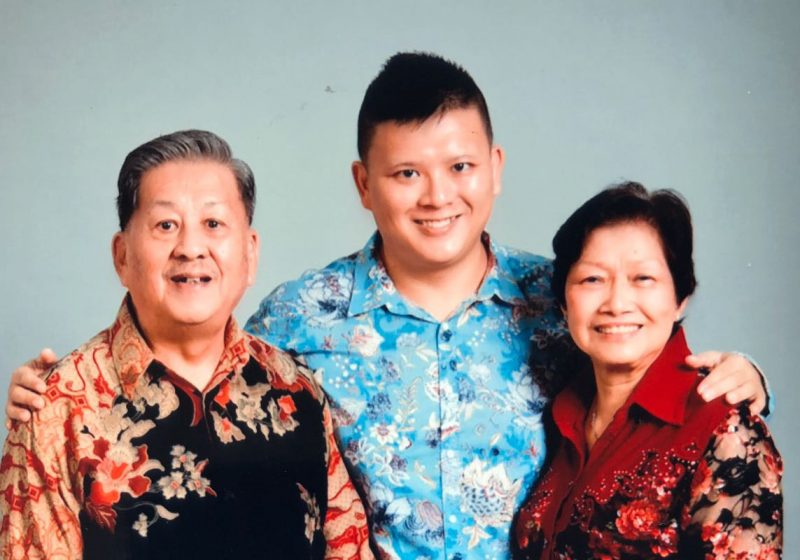

“I wish that my father would die sooner,” said my close friend with a tone of resignation. This disconcerting remark had me slightly taken aback, especially because it was made while I was still basking in the elation engendered by her special visit to cold, rainy London where I was residing at that time. What happened to the strong and rational optimist I knew? I thought.

While I was still reeling from the mild shock I received from that out-of-the-blue comment, what had ensued was an hour-long conversation about her Alzheimer’s-stricken father who was fading away into the last stages of his life. All I saw and heard in that hour was a roller coaster of mixed emotions. It seemed as though she was battling between a series of contradictory fronts:

one where she loves her father, but loathes his prolonged ordeal of dying and suffering;

one where she is distraught by watching him suffer, yet dreads losing him forever;

one where she is distressed by the prospect of his death, yet wishes that he’ll end it quick;

one where she wishes for his imminent death, yet is unsure if her life can move on after;

one where she is uncertain about her future, yet she wants her old life back; and

one where she wants life to be back the way it was, yet knows that it would be impossible because of the indelible mark his death would leave on her life.

Imagine having to struggle to reconcile these different voices in her head every single day for ten years. Boy, it must be really noisy in there. But she’s not the only one. There are millions of other caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients out there who have to deal with this internal conflict every single day.

Before we start to judge and think that people who wish death upon their ailing parents are terrible people, take a step back. Who are we to judge when we have not had the traumatic experience of watching somebody whom we love wither before our very eyes? What gives us the right to stigmatise when it is hard to do what caregivers do? What would you do when the unthinkable befalls you?

As a friend to a caregiver of an ailing parent, all we have to do is to stop what we are doing at the moment, sit down, and listen to them. They don’t need any of the cliché “Yeah, I understand what you’re going through” type of bullshit because we aren’t in their shoes anyway. Neither do they need our “sagely” advice nor our “foolproof” solutions. We’re not God and we can’t fix them. Period. Consequently, the least we can do is to be physically there for them by dropping by their place for a visit, asking them out for tea, or helping them run an errand or two. After all, as trite as it sounds, actions speak louder than words. Talk is cheap.

For voicing out the opinions of all these caregivers who never had the chance to vocalise those thoughts aloud like she did, my friend is a brave trooper. Perhaps that’s what makes her stronger than all of us. Perhaps that’s what makes caregivers extra vulnerable yet extra special. Perhaps that’s why caregivers need all our care and support too.