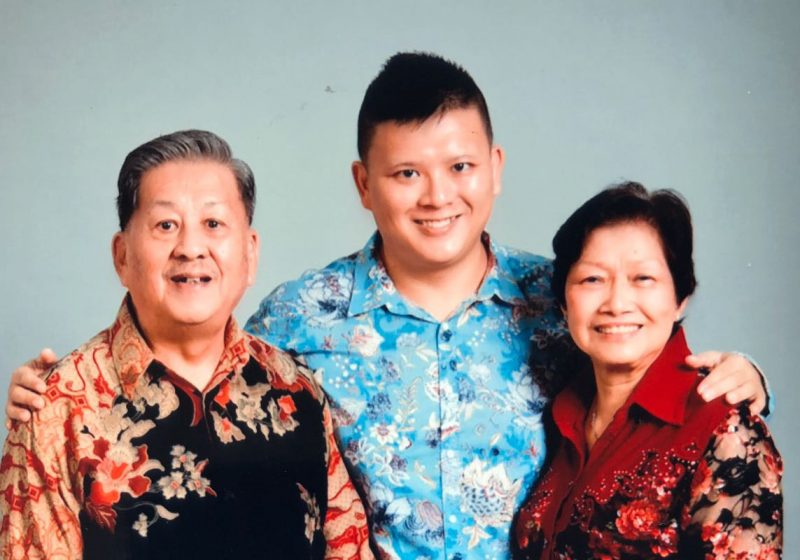

A grandson captures his day through lens as he cares for grandma who has dementia.

“This is a short exposition on what life means to us, living with a dementia patient. It is only a glimpse of what we give in our time and love everyday, to care for a person that we will cling on to desperately till the day she leaves us. And we will, hang on, and never give up. Because we never give up in our capacity to love another person.”

By Lim Mu Yao

Finding out granny has dementia

When I first knew that my granny had dementia, my heart did sink in quite a bit. Perhaps not fully understanding the full consequences of this condition, I didn’t know how and what that meant for me and my family, and my relations with her.

They say dementia is the long death of the soul, only made clearer to me to see someone that is physically there, but not.

It’s hard because it is a journey of continual disappointment to know that she isn’t the one person that you fell in love with when you were young.

The stigma of dementia

I think what contributes to this misunderstanding of what dementia really means for that loved one and those around her is simply the fact that people don’t talk about it.

They avoid talking about it like a plague and just express the superficial face of profound sympathy because people don’t understand it. I don’t blame these people, because they do not understand. More needs to be shown or done.

There was an initiative that I contributed my little voice to a year or two back, called “Before We Forget”, by Xian Jie and Jeremy, two talented and passionate youths that wanted to make difference in society. And they did, but alas, they are only one initiative amidst the many dementia sufferers in Singapore. I decided that I would be best serving myself and my fellow dementia caregivers with the openness needed to cultivate discussion. Productive or not, I’m not here to judge — all we need is a simple resonant cry that we are not out there, alone in despair of our own disappointing grief.

Caring in the moment

In our every day lives, we expect a suitable outcome whenever we take an action to solve a problem. It is not the case when you care for someone with dementia. You care only for the moment.

The love you give, and still give, every day, to that someone, is all that you will get as a reward — because you know that after a few fleeting moments, it all ends. It gives way to the stubborn self throwing a tantrum, gives way to the fear and loss in her eyes, and gives way to the worry and pleas and paranoid hallucinations.

There is none of that nostalgic happiness that comes when a sweet memory is made, only the sombre reminder that she is gone, all gone. After all that you’ve given, and then some.

And it becomes a cycle. You keep giving that love, that care, that patience, till one day, you feel utterly spent.

You have nothing to hold to, not memories, no , because it becomes to painful to remember and compare what she once was to the shell of the person that she is now.

No, you don’t give for the future, because you know she’ll just get worse. The despondent stare out of the window of an empty flat… is one of the most heartwrenching moments a person like me can ever observe as a young adult — caught in the heat of his impatience to fulfil his never-ending quest to want more from his life.

This is a short exposition on what life means to us, living with a dementia patient. It is only a glimpse of what we give in our time and love everyday, to care for a person that we will cling on to desperately till the day she leaves us. And we will, hang on, and never give up.

Because we never give up in our capacity to love another person.

Loving with Mahmah, Living with Dementia

It’s 4.38PM in the afternoon. The disorientating loneliness gives way to a mad paranoia. Tan Lee Meng, 83, is a dementia patient. She hovers by the door, anxious and worried at the news that I will be leaving her alone at home with the maid as I have to go off for an evening appointment.

A despondent disappointment sets in after my insistence that I have to go off. I offer to stay for another hour. She places her shoes and insists that she will go with me in an act of defiance. She holds a shoehorn in defence.

I call to my dad for help to find out what to do with this situation. She watches unnervingly and worryingly, as though I am plotting against her, as I talk to my dad on the phone. I snap a photo of her as she attempts to hide behind the corner of the wall.

It is frustrating. She waves and points the shoe horn at me, even trying to poke the lens of my camera. She continues with a repeated barrage of statements, still insisting that she will go with me no matter what until someone familiar comes back. She tells me she doesn’t trust the maid, whom she thinks is always trying to kill her from her large eyes.

She stands by the door, waiting. At every footstep she hears outside the common corridor, she says to herself, “It must be Han Nghee (my dad).”

I talk to her and calm her down. She sits by the sofa. Like a regular routine now, she calms herself down by eating a sugared Fruit Jelly, which she likes now. Ever since she had dementia, her eating habits have becoming like that of a child’s — always looking for something to snack on, whether it’s a french fry or a sweet.

She complains that we, as family members, do not care about her. She cannot understand why do we have to work, and cannot be always around her. I try my best to assure her that we can, even as she struggles to remember where she currently lives now, as she keeps relating back to “hwang keh sua kah” (literally meaning at the foot of Fort Canning Hill, this was her childhood home when she was staying at Boat Quay). I remind her that she currently stays in Hougang with my aunt. She looks slightly confused.

She gets kind of annoyed at my repeated snapping, hiding behind a pillow. She is shy, and does not like to be photographed in a state of distress. I talk to her, and continue snapping in Live View mode later.

Once again, I assure her that my aunt would be coming back from Malaysia the same night at about 8PM, after dinner. She keeps looking at the time on her watch. She chants repeatedly, and soon loses all sense of time. She laments that it will take very long for my aunt to come back, as she has says she has not eaten breakfast yet. I tell her that it is about 5PM, and she should be eating dinner. She looks confused, still insisting that she has not eaten for the past 8 hours. I offer her to take her downstairs for a short walk. She is quite delighted.

She hobbles down the pavement, gingerly, with me helping her. It has just rained, and hence she insisted on putting on a cardigan — a reminder that she is much more fragile than her hardier old days when I used to stay with her. She crosses the small road and I swiftly snap a photo of her. Her frail outline is plastered with the naive smile of hers. She mentions how nice it is for me to accompany her. My heartstrings tear a little, and I almost tear.

We talk at the void deck. About her routines, what it feels like staying at home, and more. She smiles upon me attempting to sing an old song, where I forget the lyrics. She laughs, and then completes the song for me. She tells me that she sings this song every week during her weekly singing sessions at the nearby Community Club.

We go back up to the house. It is a cool day, but she feels tired and hungry, even though the walk is less of a collective distance of 300 metres. I tell her to have biscuits and hot milk before dinner at 5.30PM. She lies down after eating a biscuit, and lies aimlessly, staring blankly ahead, all while breathing in her tube of Mentholatum.

I offer to turn on the karaoke disc for her. It is filled with traditional chinese folk songs from the 1940s-50s era. I sing along with her, she forgets the moment, and tells me that she is thankful for my presence. She tells me that I’m the best, and that she loves me. In all her weakness, that moment of tenderness shines, and I smile. That smile is a moment of profound, loving acknowledgement.

But the moments are fleeting, and they don’t last. She watches emptily, with the gloomy white light outside streaming in, softly. This is her default pose of sorts, hand struck up due to an accident a few years back that broke her arm. Many days are spent like this, waiting for the only few people she knows to come back to her side. With dementia, her insecurities and fears are amplified, and make the waiting seem even more agonising. I make a resolute promise to myself to continue loving.

Dad calls. She is happy, because it is an assured voice she knows on the line. Even though we monitor her via a webcam, she does not know or feel our presence. Because she forgets that she is loved, and seen, and felt by us. But in those fleetingly happy moments like this one, it is all worth it for us.

So this is us. My bond with her runs deep, cultivated at the excitement of being able to stay over at her place during the school holidays. I enjoyed those moments, where I would just enjoy her cooking, talking and accompanying her whenever she went, and helping her out with the household chores.

But those days are over, and only memories remain. And even then, I’m not sure if she remembers.

But I do, and I don’t stop loving.