Ambiguous loss differs from the experience of death because the loved one is still present. There is a lack of finality that typically occurs in death, as a caregiver experiences a loss that is gradual.

By Feylyn Lewis

The two types of ambiguous loss

Ambiguous loss, as coined by Dr. Pauline Boss, refers to the loss a person experiences when there is a lack of resolution or clarity. Originally, Dr. Boss posited the theory of ambiguous loss through studying the families of soldiers missing in combat. There are two types of ambiguous loss. The first refers to when a person is physically present but psychologically absent, as with those with Alzheimer’s Disease or dementia, certain mental illnesses, or substance abuse issues. The second type occurs when an individual is psychologically present in the minds of the family but is physically absent, e.g. a missing person.

The experience of ambiguous loss may be linked to other ill health effects such as depression, anxiety, guilt, substance abuse, and self-harming behaviours. Young adult caregivers are particularly likely to experience the former kind of loss, dependent upon the health condition of the person they care for.

Disenfranchised grief

Ambiguous loss differs from the experience of death because the loved one is still present. There is a lack of finality that typically occurs in death, as a caregiver experiences a loss that is gradual. Our society generally does not give ambiguous loss the same weight as death because the person is still living, referring to what research has called “disenfranchised grief”.

However, the ambiguous loss is significant and detrimental. Caregivers are forced to continuously grieve the loss of the person they once knew and loved while also providing care for them.

The impact on young adult caregivers

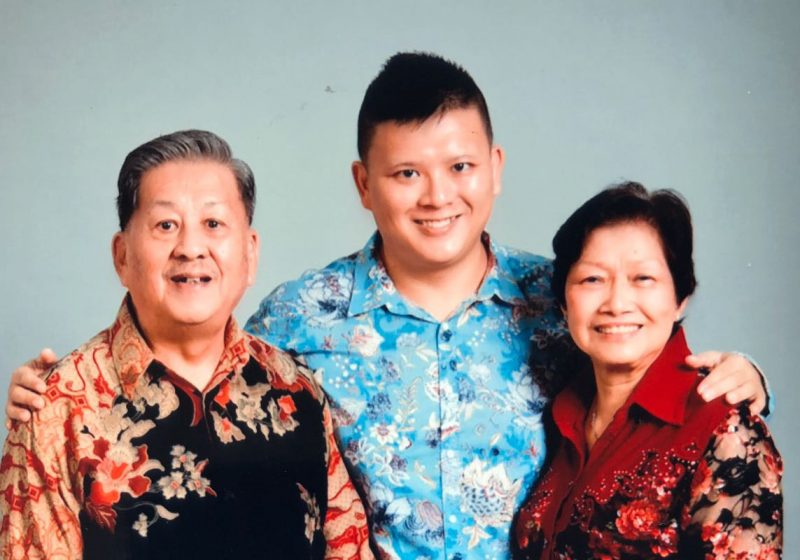

Young adult caregivers, likely because they are providing care earlier in life than they might have expected, experience a complex ambiguous loss: they grieve both the loss of the person they loved, and also the loss of their identity in relation to the loved one. Every time a young adult performs a caregiving act, be it reminding their loved one to take their medication, or paying the household bills because the loved one no longer has the mental capacity to do so, they are reminded that the person they knew is gone.

Other research has found that caregivers may be preoccupied with how their loved one used to be, and when considering the present, they may determine that their loved one is “another person”.

Furthermore, their roles become more than sibling, child, or grandchild, but expand to include “caregiver”. For many young adult caregivers, this may mean a transformative shift in their perception of their identity within the family.

In my research with young adult caregivers, I often find that they are forced to come to terms with a loss of their “normal” interactions with their loved one. Many say that they feel like the “parent”, instead of the “child”. In the midst of navigating the complicated life choices of young adulthood (relationships, education, careers), they feel like they must “figure life out” on their own.

Caring for a loved one and managing social norms

Young adult caregivers are also in the unique position of grieving the loss of their future plans with their loved one. Suzanne[1], a 26 year old young adult who provides care for her mother with early-onset Alzheimer’s, was particularly troubled by the thoughts of her future wedding: “a traditional part [of a wedding] is your mom. And she’s not gonna be here. She’s not gonna mentally be here, even if she’s physically here.”

Suzanne had to grapple with altered expectations for her mother’s role in future life events, while also continuing to perform the social norms for her age group− attending her friends’ weddings. Faced with the desire to express happiness for her friends while simultaneously feeling deep sadness over her loss, Suzanne became emotionally overwhelmed and found herself hating weddings, a life event she once greatly looked forward to.

Other young adult caregivers find themselves in similar positions: graduations, the birth of children, and other major life events must be anticipated knowing their loved one may not be “present” to share in the moment.

It is ok to reach out for help

Young adult caregivers experiencing ambiguous loss should take their feelings seriously and consider seeking professional mental health support. A counsellor or psychologist can assess the caregiver for their level of grief and their capacity for resilience. Therapy can help a caregiver find meaning, live with uncertainty, and redefine relationships and identities. Discovering hope through new life plans and dreams can strengthen a young adult caregiver’s ability to face the future.

[1] Names have been changed.

Feylyn Lewis is a post-doctoral research fellow at the University of Sussex in England. Her doctoral research at the University of Birmingham focused on the identity development of young adult caregivers living in the United Kingdom and United States. She was also a young caregiver for her mother during her childhood.